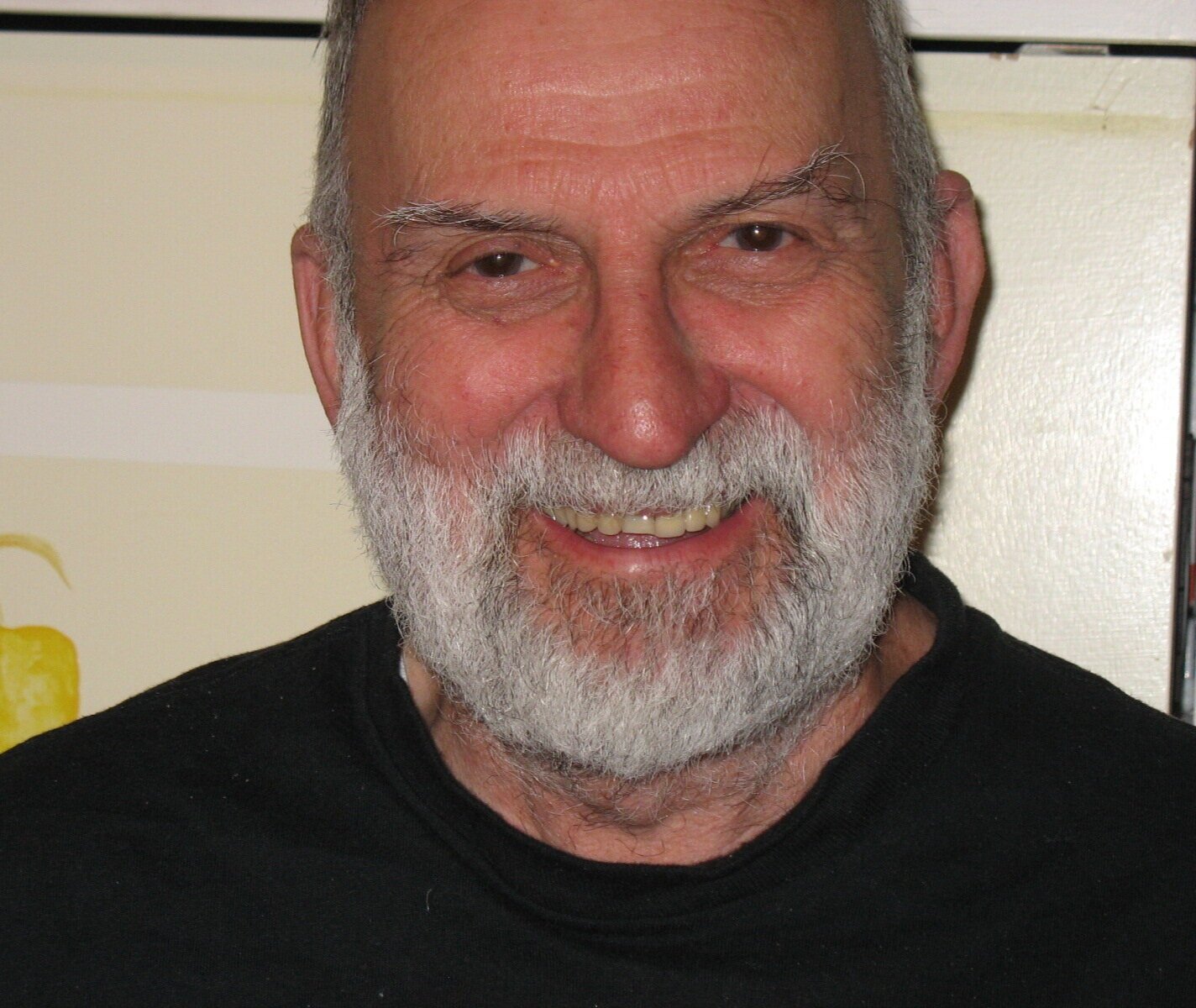

Profession: Poet

February 9, 2021

Profession: Poet is a new monthly blog feature exploring craft and identity in poetry by Hanoch Guy, who writes poems in both English and Hebrew.

SUBMISSIONS, REJECTIONS

Take a moment to think about your submissions process.

What do you think and feel about poetry submissions?

A waste of time.

Intimidating.

Slim chance of acceptance.

Worth a try.

Where do I start?

Throughout my career, I have been convinced that submission of my work is essential to me as a poet.

There is no great benefit to pursue a consistent submission stream.

*

I’d like to offer my own experience.

On July 1, 2016, I had the crazy idea of giving myself a challenge to send 100 submissions in 100 days.

I completed it.

Here are the results:

42 rejections

35 acceptances

23 no responses

At the end of the challenge, I was exhausted. During the experiment, I was not able to do anything else.

When I expressed my disappointment to a fellow poet, he assured me that that was a very good outcome.

My rules for submissions are:

I aim to send to magazines that respond within 3–4 months.

I read poems in recent issues of magazines I am interested in to get an idea of what they publish.

I only submit to magazines online that may have a print issue.

I usually submit to calls for a group of themed poems.

When I get a rejection, I send the poem to another magazine the same day.

*

Consider that most magazines have a staff of only two or three people, so expect a short form letter and don’t expect feedback.

In all the years I’ve been sending out poetry, I have received only two letters of positive feedback and two negative ones.

Bottom line: How should you submit?

It is clear that submitting is hard work and very time-consuming.

If you do online searches, you will find out, as I did, that it can be a long and drawn-out process.

In general, you should look for places that publish poets you admire. It is a good guideline to submit to places that align with your type of poetry, with your style and aesthetic, and places where you think your poems would be at home.

Here are some of the resources that may make your submission process more efficient and focused, although these will also be time-consuming and take some dedicated research.

Poet’s Market is like Old Faithful and has been published for about thirty years. It is the most trusted guide to publishing poetry. Want to get your poetry published? There’s no better tool for making it happen than Poet’s Market, which includes hundreds of publishing opportunities specifically for poets, including listings for book publishers, publications, contests, and submission preferences.

Poet’s Market also has articles devoted to the craft and business of poetry, featuring advice on the art of finishing a poem, advice for putting together a book of a poetry, promotions, and more. You’ll also gain access to a one-year subscription to the poetry-related information and listings on WritersMarket.com, lists of conferences, workshops, organizations, and grants, and a free digital download of Writer’s Yearbook, featuring exclusive access to the webinar “Creative Ways to Promote Your Poetry.”

Another good resource is Poetry Markets, where you can find places to submit whether you are a beginner or a seasoned poet.

Another source for poetry information is Poetry Super Highway.

My favorite local place to submit is Philadelphia Poets, edited by Rosemary Cappello, who is very generous with her feedback and hosts an annual reading that follows the yearly publication of the print issue.

An instructor once told me, “Unless your floor is littered with submissions and rejections, you did not do the job.”

What do you think?

I wish you good luck in your submissions.

Please share your experiences of submissions and rejections in the comments section.

Hanoch Guy Ph.D, Ed.D spent his childhood and youth in Israel. He is a bilingual poet in Hebrew and English. Hanoch has taught Jewish Hebrew literature at Temple University and poetry and mentoring at the Muse House Center. He won awards in the Mad Poets Society, Phila Poets, Poetry Super Highway and first prize in the Better than Starbucks haiku contest. His book, Terra Treblinka, is a finalist in the North Book Contest. Hanoch published poems in England, Wales, Israel, the U.S., and Greece. He is the author of nine poetry collections in English and one Hebrew book.