POeT SHOTS is a monthly series published on the third Tuesday of the month. It features work by established writers followed by commentary and insight by Ed Krizek.

Hard Rain

by Tony Hoagland

After I heard It's a Hard Rain's Gonna Fall

played softly by an accordion quartet

through the ceiling speakers at the Springdale Shopping Mall,

then I understood: there's nothing

we can't pluck the stinger from,

nothing we can't turn into a soft drink flavor or a t-shirt.

Even serenity can become something horrible

if you make a commercial about it

using smiling, white-haired people

quoting Thoreau to sell retirement homes

in the Everglades, where the swamp has been

drained and bulldozed into a nineteen hole golf course

with electrified alligator barriers.

You can't keep beating yourself up, Billy

I heard the therapist say on television

to the teenage murderer,

About all those people you killed—

You just have to be the best person you can be,

one day at a time -

and everybody in the audience claps and weeps a little,

because the level of deep feeling has been touched,

and they want to believe that

that the power of Forgiveness is greater

than the power of Consequence, or History.

Dear Abby:

My father is a businessman who travels.

Each time he returns from one of his trips,

his shoes and trousers

are covered with blood-

but he never forgets to bring me a nice present;

Should I say something?

Signed, America.

I used to think I was not part of this,

that I could mind my own business and get along,

but that was just another song

that had been taught to me since birth-

whose words I was humming under my breath,

as I was walking through the Springdale Mall.

Tony Hoagland’s “Hard Rain” is an indictment of US culture as it stood in the late 1900s, before his death and which still stands today. Most of us are familiar with the Bob Dylan song “It’s A Hard Rain’s A Gonna Fall”. Dylan’s version is also an indictment of US policy and culture. Yet heating this emotionally charged piece reduced to Muzak makes Hoagland recoil (…there’s nothing/we can’t pluck the stinger from. /) Hoagland goes on to continue to hold US America accountable for its actions.

Whether it’s using Thoreau to sell retirement homes or trying to tap into the hearts of a TV audience (You can’t keep beating yourself up, Billy…/About all those people you killed---/You just have to be the best person you can be, / one day at a time.) Do any of us really forgive twenty-year old Adam Lanza for killing twenty-six people including twenty children in Sandy Hook?

Finally Hoagland switches from the specific to a general call to awareness (/his shoes and his trousers/are covered in blood-/but he never forgets to bring me a nice present;/ Should I say something? / Signed America/) The stanza which contains these lines is key to the poem. Isn’t that what US America does? We go into various countries to strip them of their natural resources (Oil, Minerals, Trees) and fight wars for “independence” in these countries, ultimately bringing back the booty to the US.

We are all part of this says Hoagland (I used to think I was not a part of this/…? but that was just another song/ that had been taught to me since birth-/). Hoagland then includes himself in his indictment (…? Whose words I was humming under my breath,/ as I was walking through the Springdale Mall.) Who among us is without blame?

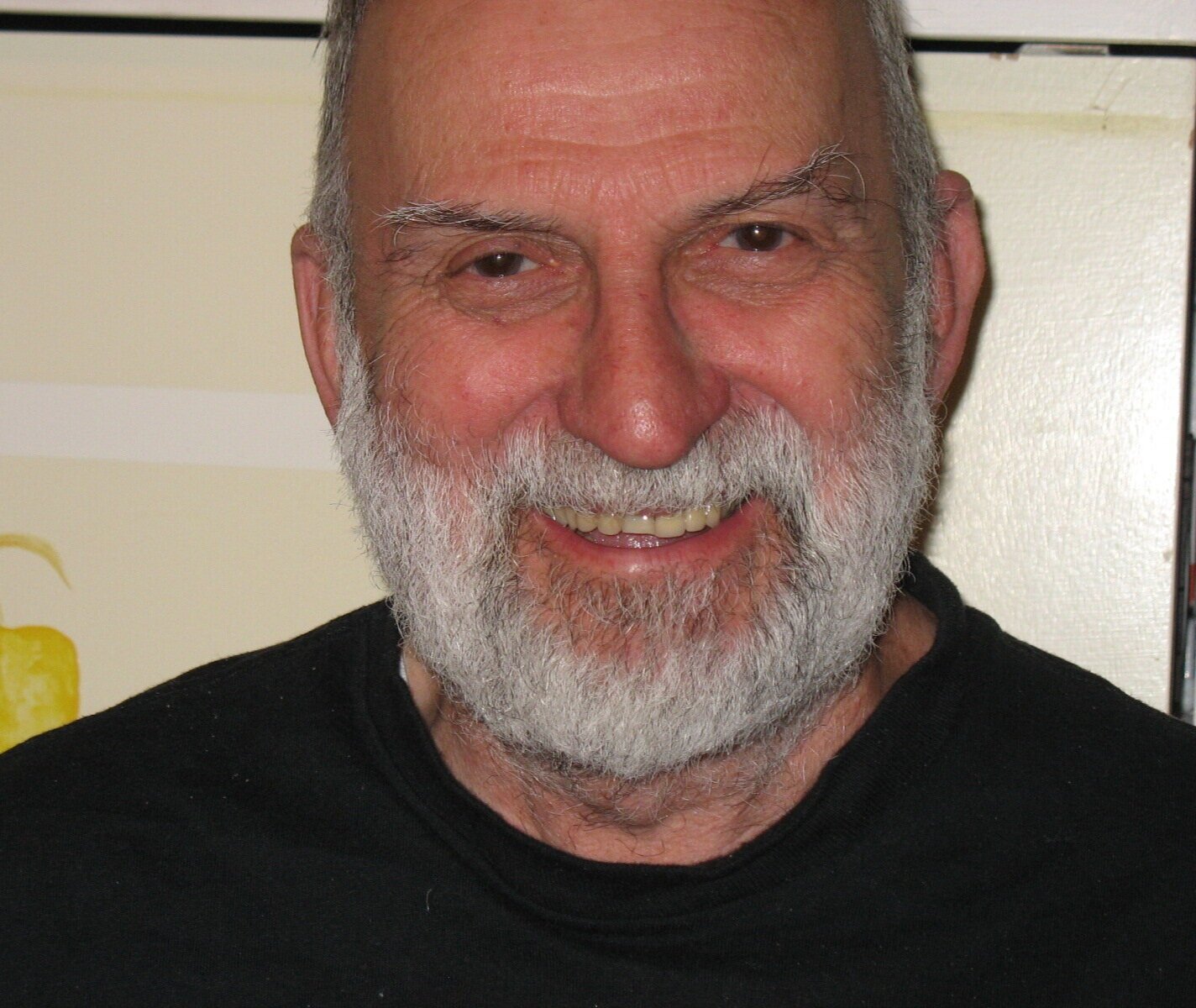

Ed Krizek holds a BA and MS from University of Pennsylvania, and an MBA and MPH from Columbia University. For over twenty years Ed has been studying and writing poetry. He is the author of six books of poetry: Threshold, Longwood Poems, What Lies Ahead, Swimming With Words, The Pure Land, and This Will Pass. All are available on Amazon. Ed writes for the reader who is not necessarily an initiate into the poetry community. He likes to connect with his readers on a personal level.