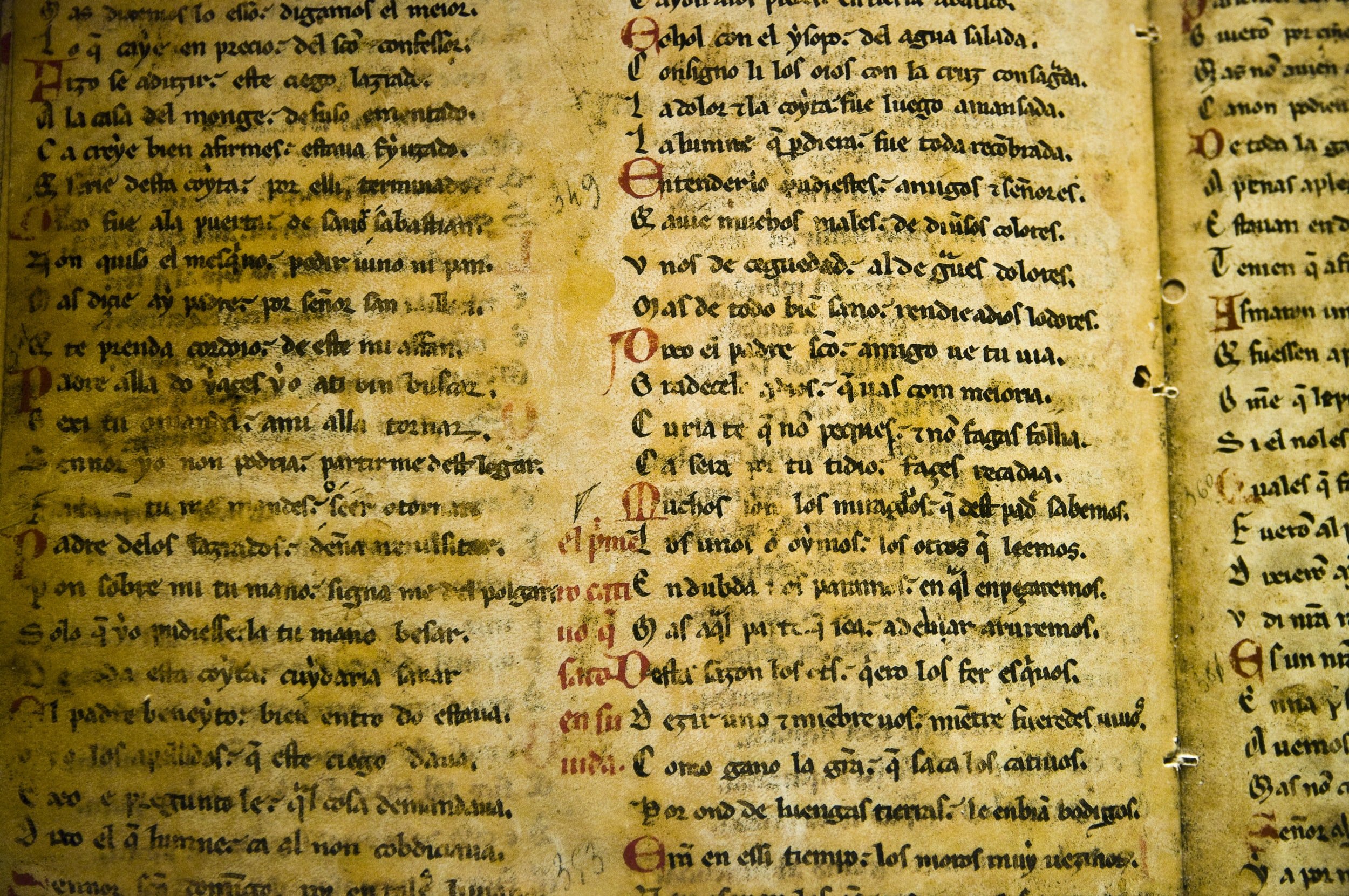

This is another bilingual edition of poetry, in the original and in translation: my favorite kind. Even if you don’t know the Russian alphabet (Cyrillic is based on Greek, with a lot of recognizable letters but also some “false friends” – Н, for instance, actually makes the sound N), you can see the shape of the original: the length of each line, how many words per line, and sometimes a few words in Latin.

J. Kates, the translator, is himself a poet, and his introduction before the bilingual selection of poems includes some very capable wordplay. When he writes that elements of Yeryomin’s work “compel me to compile,” you know it’s on purpose. Yeryomin’s name could also be spelled “Eremin,” but using the Y makes it clearer how to say it, with stress on the o in the middle; the cover of his Russian book has Ерёмин, where ë is “yo.” Perhaps nomen est omen à wouldn’t such a beautiful name make you want to do things with language? Yeryomin was born in the North Caucasus in 1936 but grew up in Leningrad (now St Petersburg); he was friends with Joseph Brodsky (b. 1940) before the USSR threw him out, is a playwright and translator, and had hardly any work published in the USSR, though some in the émigré press, and more in post-Soviet Russia.

The introduction would be useful for teaching the volume, with information about Yeryomin’s biography and publication history, but it doesn’t mention that his perpetual title (as the intro notes, for all but one of the books he published in Russia), СтихотворениЯ, itself offers some word play. It means “Poems,” but the final letter я that makes the word plural is capitalized, activating the other meaning of я = the pronoun I (not usually capitalized in Russian, though if it weren’t capitalized here no one would catch it). How could you translate that, really? If you know Latin or Italian or any other language where plurals end in -i, you could play this game in English too.

As the title suggests, the book presents verse written over 60 years, which Kates says he has been working on for 30 years (and is still working on); a number of the translations included have been published in earlier editions and places. Kates’s intro notes that Yeryomin began writing rhyming poetry but later stepped away from that. The first poems (dated 1957) do rhyme, but in very slanty ways, with nervous and jumpy rhythms. Kates frequently strives for great precision in word choice (“Боковитые,” p. 14, becomes “Polyhedral”), but otherwise he prioritizes rhythm over rhyme. It’s too bad in a way, because when early Yeryomin switches away from rhyme the reader of the English won’t notice the change. Kates has written elsewhere about the different status of rhyme in Russian poetry: even now it’s more common than rhyme is in serious Anglophone poetry. He suggests that therefore it is more stylistically neutral not to rhyme when translating poetry into English. True, perhaps—or at least arguable—but it does mean that a poet who sometimes uses rhyme can be shortchanged in new versions. In one early poem Kates misses the rhyme, which has already grown more subtle, and misreads снегá (‘snows’ plural) as снéга (‘of snow,’ genitive singular). I regret that he rendered “обыкновение монад” (literally “habitualizing of monads,” p. 88) as “everyday monad” (p. 89), though I don’t know how “everyday-izing” could be rendered poetically: it’s all very well to critique a translator’s decision if you can’t offer a better solution. On the whole, though, Kates’s translations are truly scrupulous, with only a handful of misreadings (or debatable choices?) in the course of all these pages.

Yeryomin uses sound gorgeously in some poems, with internal soundplay, agglomerations of sounds, half-rhymes or series of words all with the same stressed vowel. There is a feeling of strict diction, but not dense and dry. Some of the early poems have a Mayakovsky feeling in their use of sound, especially in the inexact, sort of snarky rhymes, and that spirit of Mayakovsky seems to resurface even later in ludic play with the language. None of the poems have titles, which is quite common in Russian and some other traditions (…though if I try it with something of my own the critique group lets me have it). A number of poems do have dedications, which could stand in for titles; several of these are to well-known poets, plus a few to someone whose last name makes clear that they’re related to the poet. More importantly, every single poem gleaned from this sixty years of writing has the same form: eight lines. To the poet reading this now: can you imagine writing that long in only one form? A series of sonnets, okay, but sonnets alone for 60 years? Somehow writing only haiku makes more sense, but that’s because of the traditional spiritual dimension, the reflection of spiritual discipline. – I recall being told to write haiku by elementary school teachers who supplied only the syllable rules, 5-7-5, and maybe maybe an authentic example, but no explicit description of what haiku DO in Japanese. I you ever sat there at your desk wondering whether to squander a syllable on the word “the”—or worse yet, two syllables on “of the”—then you have some experience with what you face trying to make a metrical translation. But back to the spiritual dimension: Yeryomin’s poems, though not a bit like haiku, do reveal a spiritual aspect. Some seem inspired by natural science, with its gorgeous Latinate or compound terms, while others note the Bible verse that inspired them, and many toy with the interaction of word and Word.

The constant eight-line form enables some things: the switch away from rhyme, already mentioned, is more noticeable; it’s more striking when one line is much shorter; the very visually comparable poems reveal other kinds of shifts in what is going on. The rhythm is most often iambic (ta-PUM, ta-PUM, ta-PUM) (…not for nothing did Sylvia Plath play with the term of art, citing her heart’s brag “I am, I am, I am”), and Kates with his sensitive poet’s ear generally observes this, giving the translations a sculpted beauty even if they don’t rhyme. Some lines are quite beautiful, especially juxtaposed with the original’s pulse. Although English tends to offer shorter words (especially the likes of the), which can clutter a poetic line, Yeryomin’s use of specialized vocabulary allows Kates legitimate access to some long Latinate words that balance the length. (Actually, even a long word in English can have multiple main and secondary stresses—reflecting a relationship to Scandinavian rhythms?—so perhaps the length of each word is less an issue than in a language like Russian that has only one stress in most words, however long.)

Author and translator clearly share a sense of humor; the words “равнины черны, как раввины” (“flatlands … rabbis,” p. 18) are visibly similar, even if you don’t know the language. Kates responds to the soundplay rather than providing the precise meaning (“[the] flatlands black as rabbis”) and gives us “ravines as black as rabbis,” not bad at all (p. 19). Some solutions are triumphant, like “semibird and semiburden” (p. 71)—I imagine Kates showing this to Yeryomin, and Yeryomin saying, thoughtfully, “All right, my friend, you are worthy to be my translator.” Elsewhere, Kates has a superb sense of the necessary stylistic level, as when he renders “сиречь” as “to wit”—archaic but not incomprehensible—or “пилигрим” as “palmer” (“pilgrim,” the cognate word, has some less relevant associations, especially for a translator who lives in New England).

Here’s the poem from which I drew that last-but-one example:

М. Ереминой

Течение вытачивает рыбу,

Вынашивает птицу ветер,

Земля

(Неповторимы дни Творенья,

Поскольку вечны, сиречь закодировано

Во всякой тварной матрице

Несовершенство воспроизводимого.)

Свидетельствует абсолют зерна.

1998

for M. Yeryomina

The current spins the fish

The wind bears the bird,

The earth

(Not repeating the days of Creation,

Considering them as eternal, to wit

The imperfection of reproducing

Is encoded in every creaturely matrix)

Certifies the Absolute of the seed.

1998 (pp. 92-93

And another, earlier one, with wonderful Mayakovskian slant rhymes:

Сшивает портниха на швейной машинке,

подобно дождю, голубое с зеленым,

Дождю, который окном изломан,

Как лодкою камышинки.

Гром за окном покашливает.

Капли дождя к стеклу прилипают,

Полузеленая каждая

И полуголубая.

1957

The seamstress stitches on a sewing machine,

Light blue with deep green, like rain,

Rain broken by the window

As reeds are broken by a little boat.

A thunderstorm coughs outside the window.

Raindrops cling to the glass,

Every single one of them half green

And half light blue.

1957 (pp. 16-17)

The translation doesn’t reproduce the rhyme, doesn’t strive for the inconsistent amphibrachs (pa-DUM-pa) of the original, but it has good poetic qualities: the rich s-sounds of the first line, the internal rhyme of green with machine, the shifting rhythms (note the lovely iambic pentameter in the fourth line). The stylistic level is appropriate: not too serious; that little passive “by a little boat” runs parallel to the archaic instrumental ending of лодкою (rather than the standard лодкой—if you’re wondering).

And a final example from among the later poems in the book:

И всяко было слово — и наскальным, и резьбой

По кости, и на писчей глине выдавленным,

И на папирусе, пергаменте, бумаге, и берёсте

Начертанным, и закодированным

(Тире и точке, флажный семафор и прочее),

И оцифрованным. И было слово

Явленное и, быв расколото в сердцах,

По памяти воспроизведено.

2017

Исх. 32:19

And each word was—on rock, and in carvings

On bone, and on extruded clay tablets,

And on papyrus, parchment, paper, and birchbark

Inscribed and coded

Dash and dot, flag semaphore, and so on),

And digitized. And the word was

Made manifest and, having been riven in their hearts,

Recreated from memory.

2017

Exodus 32:19

The Bible, again, provides an important subtext for many of Yeryomin’s poems, and Kates handles the style confidently: “the word was/Made manifest…”

The book is handsome if unassuming; there are hardly any typos though I did find a few (more in the Russian, less in the English). Besides the informative introduction, there are no explanatory notes, but a bilingual table of contents is provided in the back, where a Russian publisher would put it.

This book was published before Russia invaded Ukraine in February; the introduction might well read differently if it were published now. Born in 1936, Yeryomin is now around 86 years old; none of the poems in the book address the Russian annexation of Crimea, which had the effect of splitting the Russian intelligentsia—some people condemned it, others defended the move. If Yeryomin is writing about the situation today, I hope Kates is on the job with a translation