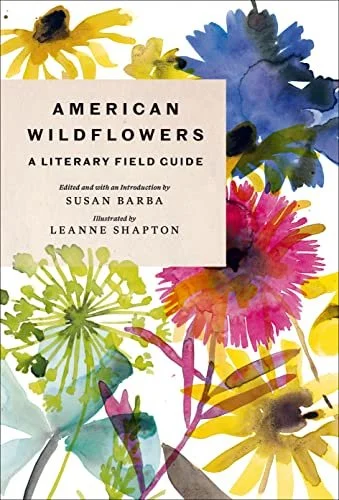

American Wildflowers: A Literary Field Guide

Harry N. Abrams Press

$21.60

You can purchase a copy here.

Reviewed by Jennifer Schneider

From Dolly Parton to Tom Petty and from Lady Bird Johnson to neighborhood garden clubs, the wildflower intrigues across time and often just in time. In its many forms, the wildflower has the potential to ignite and invite both imagination and exploration with and of all senses. It’s no wonder. Given their incredible ability to support ecosystems, pollinators, and awe – often all at once, as well as to ignite a full range of sensory experiences, the wildflowers’ variety is part of their annual and perennial appeal.

American Wildflowers: A Literary Field Guide captures and curates the wildflower and its many dimensions. The collection is edited by Susan Barba (also the author of the work’s Introduction (9)) and illustrated by Leanne Shapton. The 340-page anthology is a multi-sensory experience, with text as diverse (classic and contemporary authors across various genres, styles, periods, and places all sharing space and readership) as the work’s exquisite abstract watercolor illustrations.

Given the wildflowers’ broad appeal, it makes sense that so many authors have engaged with wildflowers through writing and in so many varied ways, including culturally, politically, and naturally. It similarly makes sense that one might choose the wildflower as the focus of a collection and field guide. What Barba has created and anthologized, though, is a bouquet of infinite surprises and that inspires both awe and admiration.

Henry David Thoreau (the subject of Lydia Davis’s essay titled Cohabitating with Beautiful Weeds (34)) may have “lamented that so few people noticed the wildflowers” (35), but Barba ensures otherwise. The collection offers opportunities and reasons to re-see. Pick one. Pick several. Pick all. No matter how many works one chooses and/or how one chooses to experience American Wildflowers, this collection will not disappoint.

The collection is as inspiring as it is informative, with authors that reach and teach with breadth as expansive as the wildflower itself. With pieces as varied as Sandra Lim’s Snowdrops (31), June Jordan’s Queen Anne’s Lace (39), Walt Whitman’s Wild Flowers (43), A. R. Ammons Butterfly weed (48), and Mary Siisip Geniusz’s Doodooshaaboojiibik (83), among dozens of others, the collection is both informative and inspiring. Organized by species and botanical family, the writings infuse connection with not only nature but also a diverse range of voices and perspectives, all while simultaneously highlighting the incredible breadth of nature’s work and wildflower-inspired writings. As Davis writes, every wildflower has a useful function (36), and the collection captures their utility along with their originality.

The work engages with the wildflower across seasons and at all stages of the life cycle.

From Devin Johnston’s Domestic Scenes (49):

A spray of toothbrushes,

stems in a mug:

a family portrait.

to Henri Cole’s Sunflower (67):

When Mother and I first had the do-not-

resuscitate conversation, she lifted her head,

like a drooped sunflower, and said,

“Those dying always want to stay.”

American Wildflowers: A Literary Field Guide offers an ideal reading for any season, stage, and state of mind. The anthology engages at the intersection of the breathtaking and the ordinary and straddles the lines often drawn between what is known and what is imagined. The collection delivers much more than a field of dreams. To read American Flowers is akin to taking a walk through a garden of finely crafted letters. The collection serves as a dictionary of both darling blooms and daring colors. The collection also offers a stem for all readers. Pieces vary in form (prose, poetry, letters, essays), time (the 1700s through the present day), location, and season. Readers can create then customize bouquets to suit all tastes as the collection’s pages bloom in unpredictable ways.

The work is also a testament to the power of nature, art, and the written word, in their many layers, hues, and shapes, to soothe, heal and unite – especially when cohabitating in similar spaces. The work is simultaneously contemplative and curious. The pages grow a garden of eclectic words, petals and ponderings, seeded with watercolor hues. Barba writes of a “hope that the anthology, devoted to writing about American wildflowers, will counter the ‘plant blindness’ of our dominant culture by exhibiting many of the flowers in the periphery of our vision” (10). Like with much of life. readers need only pause long enough, eyes open, to appreciate just how successful Barba has been. The collection not only brings plants at the periphery into lines of sight but also highlights the power of diverse voices united.

American Wildflowers is a field guide for all seasons. Both an experiment and a collection of experiments in form and function, the collection is timeless and timely -- a treat for all senses and seasons. Inhale. Exhale. Enjoy.

Jen Schneider is an educator who lives, writes, and works in small spaces throughout Pennsylvania. She loves words, experimental poetry, and the change of seasons. She’s also a fan of late nights, crossword puzzles, and compelling underdogs. She has authored several chapbooks and full-length poetry collections, with stories, poems, and essays published in a variety of literary and scholarly journals. Sample works include Invisible Ink, On Habits & Habitats, On Daily Puzzles: (Un)locking Invisibility, A Collection of Recollections, and Blindfolds, Bruises, and Breakups. She is currently working on her first series, which (not surprisingly) includes a novel in verse. She is the 2022-2023 Montgomery County PA Poet Laureate.