FOUND IN TRANSLATION

I’m excited to get to write for Mad Poets about poetry in translation. If you’ve attended a lot of the First Wednesday readings at the Community Arts Center in Wallingford, you’ll have noticed that translators of poetry (often also poets themselves) present their work from time to time. It’s a task that fascinates me: the verbal texture of a poem is so important, but every language has its own, even languages as close as French and Spanish, or German and Dutch. Every language has things it does better than any other, and you can bet those things wind up in poems. How then can a translator bring the poem into a new language, keeping it a poem instead of a prose retelling?

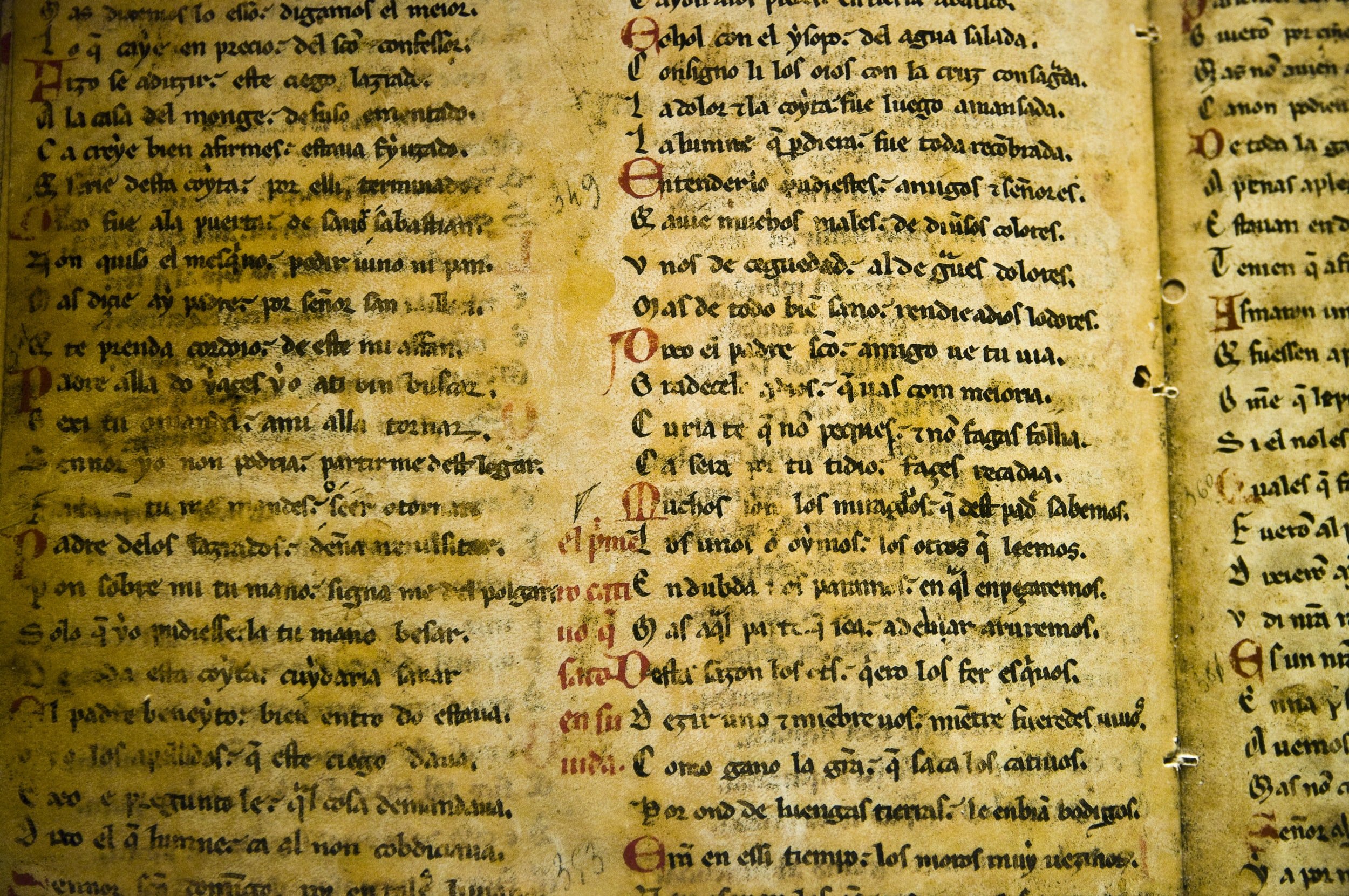

And yet poetry has exerted huge influence through translation, from Classical Greek or Latin shaping the writing of the Renaissance—or Italian sonnets spurring Elizabethan writing—to the very spare form of haiku flowering in other languages, including American English. Look closely at any big literary movement, and you’ll find translation at its roots.

For my September review of poetry in translation, I picked up a newish translation of Arthur Rimbaud. Who better to appreciate in translation than Rimbaud—that punk, that proto-Surrealist and synesthete, sailor of the drunken boat? Rimbaud, of whom we hear when we’re just a bit older than he was at his best, so that along with the joy of his verse, en français or in English, we learn that we are too late to be poetic prodigies. Only Mozart and Yo-Yo Ma are more demoralizing. Yet his most famous works are entirely persuasive: he’s the real thing.

But I didn’t like these translations. Maybe in part because the poems are presented chronologically, so you have to wade through unimpressive stuff before getting to the great poems. But even more, because I disagreed with a lot of the translator’s choices. 1) The first cycle featured the word ’Neath, an old-fashioned cheat to save a syllable that gave that line a Victorian ring. Yes, those were the years when Rimbaud’s writing flourished, but weren’t you just trumpeting his avant-garde qualities in your introduction? Though of course there are translators who carefully consult old dictionaries to make sure the word they’re selecting is attested in the language in those years. Seems an ungrateful task to me, if you can’t pipe it into a lively poem! I thought: you can’t judge a whole book by one gaffe, these were his early pieces, and ploughed ahead. 2) Lo! R’s poem “Sensation” ends with the words “heureux comme avec une femme”—literally, “happy as if with a woman”— but our translator offers “as if with a girl.” Now, “as if with a woman” (given the young male speaker who describes himself going out into the world to feel sensations) suggests sexual possibilities that, if you change it to “with a girl,” are transformed either into a more tentative exploration, maybe more exciting but less comfortable/certain to lead to happiness, or else just icky. Our translator is a much older man than Rimbaud was as he wrote (older, indeed, then Rimbaud ever got to be), so perhaps wants the reader to think of adolescent sexual experiments rather than nature’s parallel to a mature woman, but it changes the effect a lot. 3) For all his avant-gardery, Rimbaud used rhyme in pretty traditional ways, but our translator is all over the place, switching from ABAB to AABB for no reason, it seems, other than that he managed to find a rhyme that worked there. If one of my students did these things, I’d want to hear why they thought it was a good idea.

Some translators hate the way a “foreign language professor” will land on a single word and criticize the whole translation based on that word, but in this translation I found that single words (’Neath; girl) caught my attention as they sort of crystallized what was going wrong in the translation.

So I skip ahead to my favorites. “Vowels”—better, though full of choices I would not have made: “E, candeurs des vapeurs et des tentes” is given as “E, white of vapors and tents,” not trying to find some more difficult word for “candeurs” (even “candors,” or any of the words from that root: candidness?—even though English has mostly forgotten the etymology of “candidate,” wearing a white garment to indicate one’s purity and honesty), and seemingly not trying at all to preserve that floating rhythm. “The Drunken Boat”—still better: several of the stanzas do rhyme (and better not to force the rhyme if you can’t make it fly), and the stylistic of the language is nicely elevated, but the rhythm is still all over the place. You’d think: if you’re going to describe a drunken experience, it's extra important for the language to convey intoxication as well as all sorts of interesting scenery and ideas.

And so on. I’m not going to give the translator’s name, since this blog piece will be online and thus searchable, and why hurt someone’s feelings? It would be different if the publisher had asked me to evaluate the translation, or if some journal had asked for a review, but I picked this one out myself. If you decide to go out and buy a book of Rimbaud in English, or to check one out from the library, I’ll be happy to tell you which edition to avoid, or to distrust. We could meet for coffee and compare the versions we like more or less. We could pick one favorite Rimbaud poem and hash out the way WE would translate it. And of course with a famous poet like this one it’s a good thing to lots of available translations: it might offer just what a reader would like.

All of which leaves the question: Why review a bad translation? Especially for the Mad Poets Society’s blog? Yes, there’s a kind of pleasure in feeling that you know better than the translator. (Plenty of translators of poetry or of prose will admit that they were inspired to get to work by feeling that they could do better.) But the know-it-all critic is not really getting the right things from an objectionable translation: after all, irritation may be found in so many other sources! What we want from poetry in any language is what real poetry gives us: picking the lock of our minds with the right words, the right rhythms, and getting inside to dance. Rimbaud certainly does that in the original incandescent French, and probably in several other translations into English.

Poet and translator Sibelan Forrester has been hosting the Mad Poets Society's First Wednesday reading series since 2016. She has published translations of fiction, poetry and scholarly prose from Croatian, Russian and Serbian, and has co-translated poetry from Ukrainian; books include a selection of fairy tales about Baba Yaga and a bilingual edition of poetry by Serbian poet Marija Knezevic. She is fascinated by the way translation follows the inspirational paths of the original work. Her own book of poems, Second Hand Fates, was published by Parnilis Media. In her day job, she teaches at Swarthmore College.