FOUND IN TRANSLATION

I’m excited to get to write for Mad Poets about poetry in translation. If you’ve attended a lot of the First Wednesday readings at the Community Arts Center in Wallingford, you’ll have noticed that translators of poetry (often also poets themselves) present their work from time to time. It’s a task that fascinates me: the verbal texture of a poem is so important, but every language has its own, even languages as close as French and Spanish, or German and Dutch. Every language has things it does better than any other, and you can bet those things wind up in poems. How then can a translator bring the poem into a new language, keeping it a poem instead of a prose retelling?

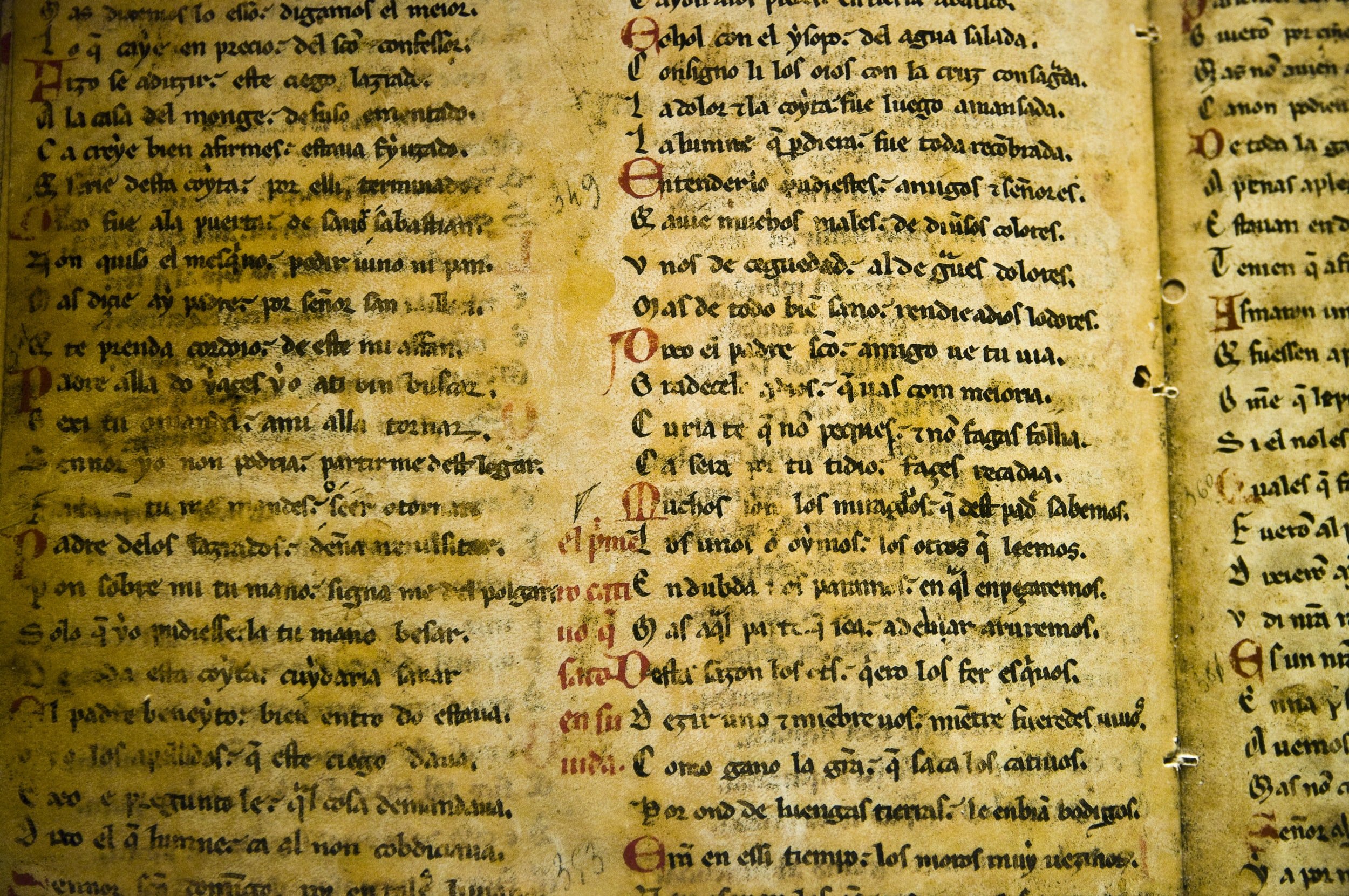

And yet poetry has exerted huge influence through translation, from Classical Greek or Latin shaping the writing of the Renaissance—or Italian sonnets spurring Elizabethan writing—to the very spare form of haiku flowering in other languages, including American English. Look closely at any big literary movement, and you’ll find translation at its roots.

Krystyna Dąbrowska, Tideline, translated from the Polish by Karen Kovacik, Antonia Lloyd-Jones, and Mira Rosenthal (Brookline, MA: Zephyr Press, 2022).

Who is Krystyna Dąbrowska? A poet, essayist and translator, born in 1979, who lives and works in Warsaw. As of late August, 2022, her Polish Wikipedia page shows four books of poetry (2006, 2012, 2014, 2018) and three books of translations, including works by Jonathan Swift and Louise Glück, as well as plentiful other translations that don’t comprise whole books.

Tideline is a bilingual edition, so anyone who knows Polish can enjoy the original alongside the translation in a typically handsome Zephyr edition: good paper, plenty of space in length and breadth for each poem (with the original facing the translation). As always, the bilingual edition can serve as a language-learning aid, or it can let the informed reader rejoice in the successful moments or grind teeth in the places where they could have done better. (How many translations have been made because the translator was disappointed in someone else’s effort? More than we might think, I think.)

Rather than an introduction, as many Zephyr bilingual editions provide, this one has analytic and informational vitamins packed into a thoughtful six-page Afterword (by Mira Rosenthal). That makes sense since someone of Dąbrowska’s age can’t yet be a Classic: it’s the poetic quality of 150 pages of poetry that buys our confidence and interest, so we’ll go on to read the Afterword. The Classic part may be coming, though: Dąbrowska has won (in 2013) the Wisława Szymborska Award and several other big poetry prizes, and her poems have been translated into 20 languages. (It’s interesting that in the U.S., where we give so little weight to translations, poets still get to list that detail: which languages we’ve been translated into. And if you, my poet-reader, haven’t yet been translated into a foreign language that you know well, it’s a very worthwhile experience.)

It’s a trick to have three different translators providing versions of the various poems—and not all are from one country: Antonia Lloyd-Jones is from the U.K. (and is one of the translators of the 2019 Nobel Prizewinner Olga Tokarczuk), while poets and Creative Writing professors Karen Kovacik and Mira Rosenthal are from the U.S. The results are pretty harmonious, nevertheless, with a consistent voice achieved across the volume. If I were a student at Indiana University, where Kovacik teaches, or at Cal Poly, where Rosenthal teaches, I would hasten to sign up for a class: the results speak for themselves.

There, the background is outlined and we can turn to the work itself. It seems clear what attracted this trio of talented poet-translators to Dąbrowska’s work. I don’t detect (with my limited command of Polish-for-reading) signs of great phonetic magic, but almost every single poem has a surprise—an unexpected detail or a proper “turn” as it unfolds. In the poem “Names” (“Imiona”), the nuns who staff a hospital each choose a watermelon in the gardener’s cold frames (yes, this one was translated by our British representative, Ms. Lloyd-Jones), each etching her name into the chosen fruit when it is still small. As the fruit grows, their names grow too (p. 13), sometimes to the point where the fruit splits and its fragrant red flesh is revealed. A pet tame hedgehog falls in love with a scrubbing brush (pp. 64-65). The poem “Security Questions” (same title in the original) opens with a list of security questions on a US embassy website, as the speaker is applying for a visa:

What was your family nickname as a child?

In which city did you meet your husband/wife?

What street did you live on at the age of eight?

What was your first love’s given name?

Noting that these are also “insecurity questions,” the speaker is inspired to think up a list of the latter:

The name of a person you’ve wronged?

Define in one word your most latent fear.

When (give year/month/day) did you find yourself waiting

for someone who meant everything but never arrived?

“The system doesn’t care” about the answer, in the end, but the insecurity questions underline the potential anxieties of a planned departure and the visa required to make that move.

Most of the poems don’t rhyme in the original (and so the translations don’t either, suitably), but when “Doormen” (“Portierzy”) opens with a more formal stanza Mira Rosenthal is on it:

Behind glass doors—they stand, obscure.

At revolving doors—they stand, demure.

At dubious gates—they stand, forbidden.

In the wide open—they stand, hidden. (p. 57)

This one goes on to note how many doormen are themselves refugees, whose relationship to doors and borders is forever complicated by that experience, even if now they can be calm and perhaps even nap behind the doors they guard.

As the book goes on, some of the poems become less lighthearted. “Siblings” (“Rodzeństvo,” pp. 76-77) describes an aged flamenco dancer, the brother of a woman (his former partner in “a celebrated teenage dancing couple”) who perished young during the war: “He told himself that if he survived/it was only to become her embodiment in dance.” Then the poem on the following page moves closer to the Holocaust in Poland:

Personal Items

The bedding is airing on the balcony.

Not her bedding anymore.

Not her balcony anymore.

Her mother’s finest eiderdowns.

Her mother who’s in a camp.

The whole family is in a camp

apart from her, she can look at her balcony,

not hers anymore, in a home that’s not hers.

Occupied by a German officer.

And his Polish lover.

Who stands before her in the hall

and shakes her head.

“I’ll give you back some personal odds and ends,

but the bedding stays.

Be glad, child, you weren’t in the apartment

when they arrested everyone,

and that I let you come here

and you’re leaving in one piece.” (p. 79)

Several of the poems make references to poet things, sometimes even to a poet: the speaker’s grandmother, out dining with a friend, is greeted by Tadeusz Różewicz (p. 84-85); we hear about doctor William Carlos Williams in his youth (pp. 136-139); the speaker comments on the authenticity of Cavafy’s bed in a house museum (pp. 100-101). That poem, “Bed” (“Łożko”), ends with four lovely, rhythmic lines describing Alexandria:

Lining the street, where boys for hire once lingered,

now theaters and fast food joints extend. Only the sea

hums like it used to hum between two headlands,

and like hands amid sheets flicker two small boats.

The later poems include addresses to a partner and poems inspired by travel (to Alexandria; to [former Soviet] Georgia; to Latin America). Rosenthal’s “Afterword” is finely and admiringly written: she is not just a fine translator, but a grateful and attentive reader, open to inspiration from the poet she is working on. Quoting Dąbrowska’s comment that she (D.) uses language as “‘a tool, a way of struggling with reality, not an end in itself,’” Rosenthal observes: “This quality poses a translation challenge: how to convey a controlled and elegant lyricism without burdening it with embellishment or mannerism” (p. 156). So many of the poems in Tideline are not only pleasing to read but also suggestive of what other poets might learn by reading them.

Poet and translator Sibelan Forrester has been hosting the Mad Poets Society's First Wednesday reading series since 2016. She has published translations of fiction, poetry and scholarly prose from Croatian, Russian and Serbian, and has co-translated poetry from Ukrainian; books include a selection of fairy tales about Baba Yaga and a bilingual edition of poetry by Serbian poet Marija Knezevic. She is fascinated by the way translation follows the inspirational paths of the original work. Her own book of poems, Second Hand Fates, was published by Parnilis Media. In her day job, she teaches at Swarthmore College.