Ekphrasis: Poems and Art

Welcome to a new Mad Poets blog, to be offered quarterly.

It’s a pleasure to write about the relationship between poetry and other art forms, to examine ways that a various creative arts relate to each other.

The term ekphrasis can be defined narrowly as writing that describes a work of art in another medium-- paintings, music, photography sculpture and the like. It can also refer more broadly to the alchemy that happens when one medium tries to define and relate to another. This could refer to poems inspired by the visual arts or music -- and also the reverse! To my mind, ekphrasis can also encompass hybrid works, like artists’ books, author/illustrator collaborations and graphic poems.

Many scholars have written about ekphrasis and there are great resources online. Though not scholar of the topic, I have had a practice of writing poetry and painting for many years. Both are essential to my creative life. These art forms interact, challenge each other and open up many questions and tensions.

My aim in this blog is to feature the work of various poets and artists, to let you know of interesting viewing opportunities and to provide some angles that might prompt your own writing.

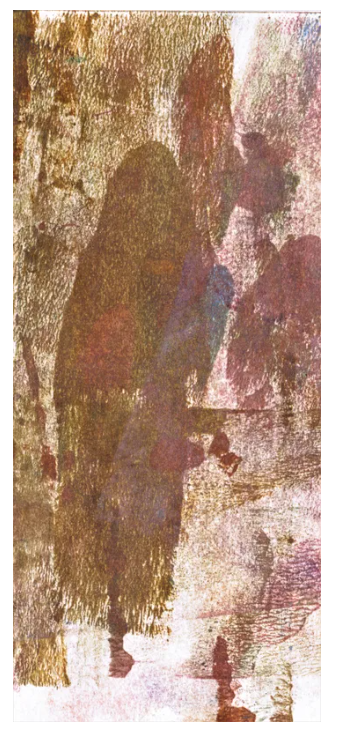

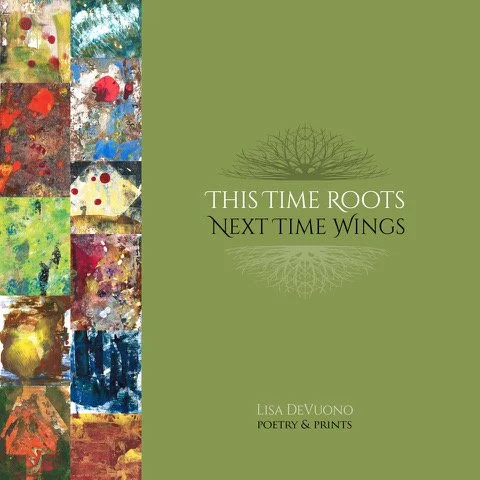

Lisa DeVuono: This Time Roots, Next Time Wings

Upside-Down World

After Rumi

Jasmine flowers jump off the roof

Old basements hide loneliness

Fifteen trucks sleep at the weigh station

The highway is a thin teepee of disappearance

Shoes slip into the ground

Wandering grows under my feet

I walk through deep space

My lap is big enough for joy

More remnants for describing fog

Words spit – fire-crackering the sky

Two by two they descend into the dream

Infinite blue, this cobalt store

Ten more times to write

What died last night can be whole today

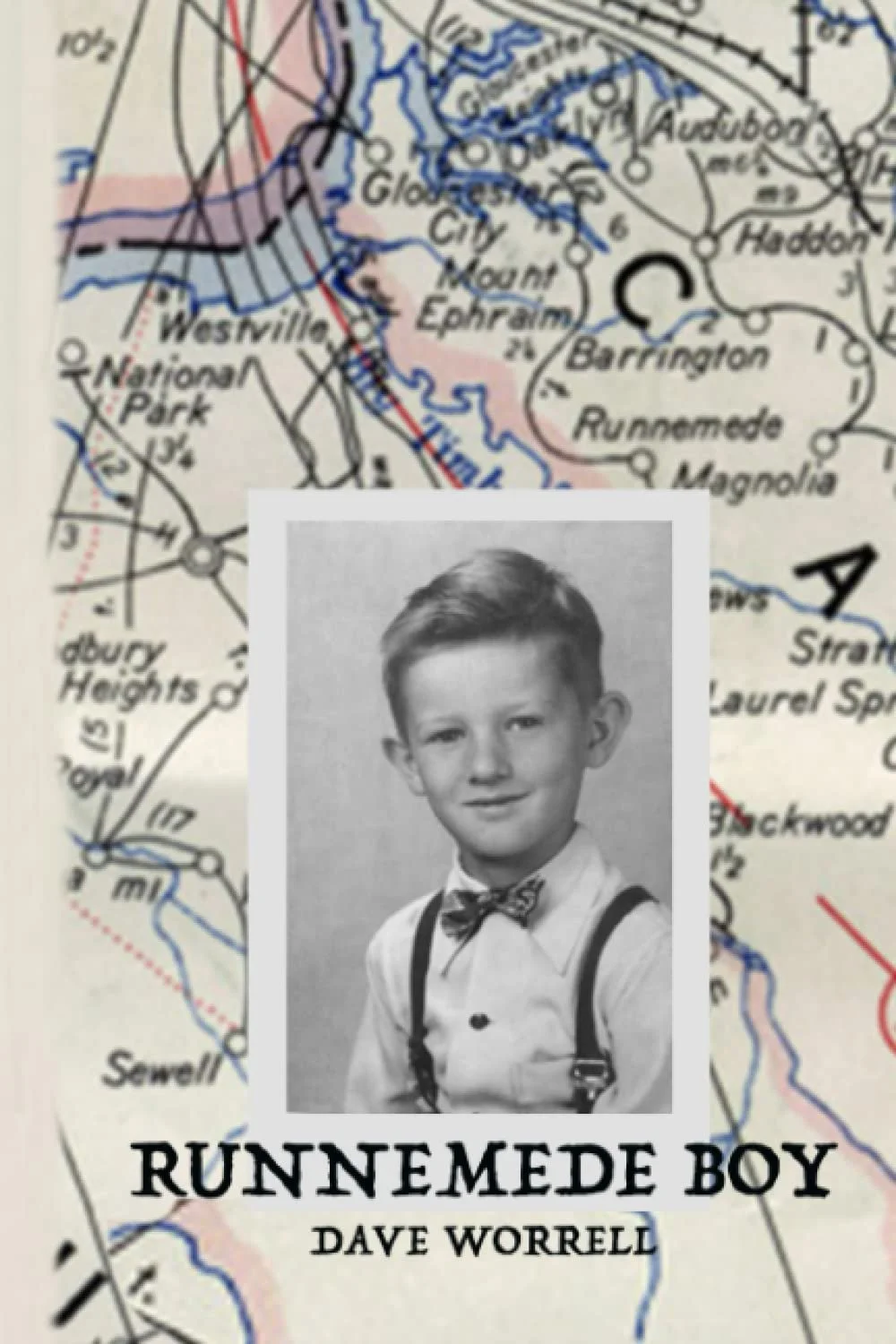

Recently, I’ve been thrilled to delve into Lisa DeVuono’s new book, This Time Roots, Next Time Wings, her fine collection of poems and monoprints. Lisa is a local poet, artist, performer, and seasoned workshop facilitator who has worked for many years with a variety of diverse communities.

Ever since meeting her years back at a poetry therapy conference, I have admired Lisa’s dedication to using poetry as a tool to deepen our understanding of ourselves and others. More recently, I was intrigued to learn about her ekphrastic practices of pairing visual images of her prints with her poems.

Creative expression has long been important to Lisa, beginning when she was in elementary school, crafting poems, covering her schoolbooks with collaged words and images and transcribing the words of admired poets. Visual art always surrounded her and her father was a jewelry designer who painted and made wood carvings.

Lisa says that the intention of her creative work is to connect. What drives her is its healing, spiritual, and transformational possibilities. She personally experienced its power and potential in 1999 while healing from Lyme’s disease. This led to her connection with the National Association for Poetry Therapy and a focus on writing’s therapeutic aspects as she began to lead workshops with different populations.

Among her many accomplishments, Lisa cofounded IT AIN’T PRETTY, a collective of women writers and performers. For ten years she coached and trained mentors through the Artist Conference Network, which supports artists in their creative projects. She has facilitated poetry workshops with teenagers in recovery and with cancer patients as well as individuals with ALS and their families. Her poetry curriculum, Poetry as a Tool for Recovery: A Guide in Eight Easy Steps, was published by the Institute for Poetic Medicine.

Visual artists whom Lisa admires are Henri Matisse, Robert Rauschenberg, Jasper Johns and Joseph Cornell, whose sculptural 3D works particularly inspire her. She has been influenced by poets Naomi Shihab Nye, W. S Merwin, Ted Kooser, Li-Young Li, and Rumi. Her husband, Michael London, is a musician and together they have performed the poetry of Rumi that he has adapted into song. Music is particularly important to Lisa, as she says that it bypasses the critic in her brain and allows her to be open to receiving inspiration.

During the pandemic, Lisa took up visual art-making intensely, creating gel prints at home and putting aside her writing for a while. She experimented making hundreds of one-of-a-kind monoprints. The meditative, playful and intuitive process of printmaking captured her imagination. And, indeed, some poems came out of all this. (To learn more about gel prints, which involve using a gel plate and paints to print on paper, there is much information available online.)

Ghost

I am out of tricks today

no new ways to make you remember

who I am to you – you’re the mother, I’m the daughter

cajoling words on a swaying rope bridge

where our collective memory might hold us

in the middle of this uncertain footing

where illumination of love might shine

all over the world, stars are dying out

just because there is a crack in everything

doesn’t always mean the light gets in

You are the very disappearance of light

a person traveling backwards

into a tiny pinhole of knowing

down a long tunnel of narrow

To follow you there

I must forget who we’ve been

get small again

like a child in the dark

shine a flashlight to my face

“See Mama, I’m the ghost.”

It was fascinating to hear Lisa talk about her approach to printmaking, and gave me much to think about vis-à-vis how visual artmaking might relate to writing poems. She loves playing with color and seeing how mark making enhances images. She talks about the resulting images as springing from emotions in the body that might otherwise be hard to access. “Through an external stimulus, a valve or channel in the body gets opened energetically and needs to be expressed,” she shared.

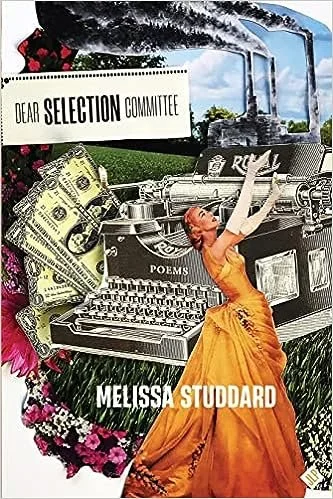

For Lisa’s latest book project, This Time Roots, Next Time Wings, she had initially thought it would be a chapbook. However, with support and advice from an artist friend, Mia Bosna, she decided to include images of her prints alongside several of her poems. She chose a larger format for the book than originally intended in order to pair images and texts. Putting the book together, she matched prints and poems and felt that this process evokes freshness-- which I felt as well seeing her poems and print side-by-side.

I highly recommend This Time Roots, Next Time Wings, Lisa’s wonderful new book, which delves into family history as well as her own journey of self-knowledge and exploration. It offers a multi-textured collection of works based on music, poetry, art, memory and connection.

For more about Lisa, including her upcoming readings -- https://www.lisadevuono.com/

Cathleen Cohen was the 2019 Poet Laureate of Montgomery County, PA. A painter and teacher, she founded the We the Poets program at ArtWell, an arts education non-profit in Philadelphia (www.theartwell.org). Her poems appear in journals such as Apiary, Baltimore Review, Cagibi, East Coast Ink, 6ix, North of Oxford, One Art, Passager, Philadelphia Stories, Rockvale Review and Rogue Agent. Camera Obscura (chapbook, Moonstone Press), appeared in 2017 and Etching the Ghost (Atmosphere Press), was published in 2021. She received the Interfaith Relations Award from the Montgomery County PA Human Rights Commission and the Public Service Award from National Association of Poetry Therapy. Her paintings are on view at Cerulean Arts Gallery. To learn more about her work, visit www.cathleencohenart.com.